“Our looking is perfected every day-but we see less and less. Never has it been more urgent to speak of SEEING. Onlookers we are, spectators…”subjects” we are, that look at “objects”. Quickly we stick labels on all that is, labels that stick once – and for all. By these labels we recognize everything but no longer SEE anything. We know the labels on all the bottles, but never taste the wine. “

Frederick Franck, The Zen of Seeing

“You learn to see by practice. It’s just like playing tennis, you get better the more you play. The more you look around at things, the more you see. The more you photograph, the more you realize what can be photographed and what can’t be photographed. You just have to keep doing it.”

Eliot Porter

When we want to take our photography to a higher level, we must learn to observe better. It is not about visiting exciting places and having wonderful subjects in front of us.

Even in the most ordinary places you may find something of interest. It has little to do with the things you see and everything with the way you see them. The more carefully you observe things, the better your pictures will become. You can only really learn how to do this when you are able to relax. As long as your mind is filled with worries and concerns, you are occupied with yourself and not with the things you want to see. Therefore, you must try to clear your mind. Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. A good start would be reading Jon Kabat-Zinn’s inspiring book “Wherever You Go, There You Are”.

Once you know how to relax, you can go on to the second step: paying attention to something or somebody.

As Freeman Patterson says in one of his books: “The trick is to learn how to switch yourself off, so you can switch your subject matter on. You have to “let go”.”

In other words, you must develop an attitude of “relaxed attentiveness”. This sounds like a contradiction in terms, and certainly it is not is easily accomplished. Nevertheless, it is well worth trying to get there.

Mindfulness is another word to refer to this state, in which we are not going anywhere or looking for anything specifically, but are one with what is surrounding us. Once we are able to “switch ourselves off”, we allow the picture to find us, instead of us trying to find the picture.

Most of us seem to suffer from sensory overload nowadays and we cannot pay constant attention to all the stimuli that we are subjected to. It is however possible to tune in to specific ones if they are of sufficient interest to us.

I remember an afternoon during one of the first photo workshops that I attended in South Africa. We stopped somewhere in the mountains near Kamieskroon and within minutes everybody was happily shooting away at rocks, trees, flowers, insects and what not. Everybody except me, that is. I was still busy trying to wind down, to relax, to “get in the mood”. Suddenly I became aware of the enormous variety of subjects and of the many ways people were responding to them: some were on all fours , one or two were lying on their backs looking up into a tree, others were sitting on rocks or in trees looking down, etc, etc. So, if I was the only one not seeing anything worth photographing, it obviously had to do with me and not with a lack of suitable subject matter. As soon as I realised this, the “what should I photograph” spell was broken and I started taking pictures just as happily as all the others.

Often one is so focused on the point of interest in the picture frame, that all the rest is not seen consciously. Apparently, the brain filters out much of the “noise” around us.

Richard Zakia (Perception and Imaging, 1997) describes this as: “We only see a small fraction of what we look at, and more often than not we “level” what we look at rather than “sharpen” it.”

One of the strongest barriers to seeing is categorizing and labeling:

– “why should I take a picture of that, it is only a nasty weed”;

– “no good photographing this flower, it’s not fully open yet”;

– “I don’t know this plant’s name, so there’s no use spending time on it”, etc.

It is only when we can leave this stage behind us that we will really see and realise that even simple, daily things can be very interesting.

As Robert Adams (Beauty in Photography, 1996) puts it: “Bell peppers would seem to be about as limited as any subject matter could be, but in fact how unlimited they are when photographed by Weston.”

Another attitude problem is caused by the “been there, done that” syndrome: you look at something and think: “Well, yes, I have seen this many times before and I do have pictures of it, so why waste time looking at it again”. (Never mind that it is not exactly the same thing; it is a different time of day, another season etc.). It may even be very useful to return to the same subject several times, because this will force you to look at it in new and unusual ways.

We need to have something like the receptiveness of a child looking at a thing for the first time. We can only hope to regain this wonderful innocent vision by breaking away from rigid, conventional ways of seeing and thinking.

A good way to improve your seeing is to look regularly at possible subjects through a small opening cut in a piece of cardboard. The opening should be about 10 x 15 cm (with the same aspect ratio as your viewfinder.

Because drawing sharpens the visual senses, one of the best ways to learn how to see better would be to attend a couple of art classes or study a book on learning how to draw. This may sound strange at first, but when you give it a try, you will find out that it really works. You will not only start looking at things in a different way, but also see things you never saw before.

The above is a somewhat modified chapter of my ebook on plant photography. The rest of this post is devoted to a recent example of looking and seeing “out of the box”.

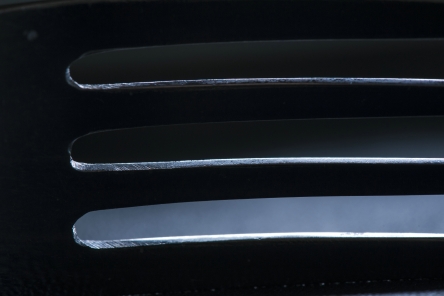

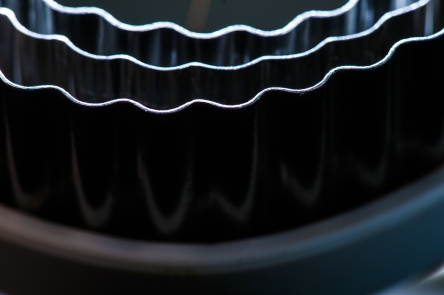

Last Wednesday our small local photo group had its monthly meeting. All the members had to show a couple of pictures of kitchen implements. Hardly an interesting subject one may think, but its very mundaneness had forced us to look at things in a different way.

Some of the results were quite surprising. The following pictures were part of my contribution : there is no direct relationship with plant photography, but the pictures give you a good idea what can happen if you let go of pre-conceived notions of what things should look like.

The same fork, seen from above. Lit partly from the back with small flash.

Very nice read and although not a crack photographer I do know the “value” of regular exercise in a field, say birding, we do not get to it that often, and it always takes a little time to really open up the senses to “see” in the bushes, and not just scan over the top of everything. Ryan

And remember, the more you do it, the better you will get at it.