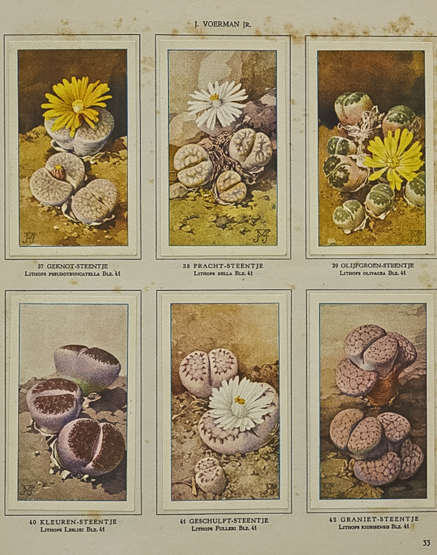

The drawings above, were in the first book on succulents I ever saw. They showed plants apparently called “living stones” and made such an impression on me that over sixty years later, I still know exactly how and where I came across them. Because they looked so peculiar, at first I thought they were figments of the artist’s imagination, but I soon found out that plants like these really existed and this was the start of a lifelong fascination.

From the beginning, one of the most intriguing aspects of succulents to me has been the way in which they manage to survive in the most difficult situations. Over time I visited many countries to look for succulents in their natural habitats and this only added to that feeling of wonder.

In 2001, my wife and I moved to South Africa, which gave me more time and opportunity to see and photograph succulents on their home turf.

Some years later, I was asked by one of the local garden clubs to give a talk on succulent plants. Over the years, I had often done this in the Netherlands and neighbouring countries, but this was the first time I was asked to do so in South Africa. I quickly realised that the invitation was both a challenge and an opportunity to give a completely different talk from the ones I was used to give. When I thought about why exactly I was so intrigued by these plants, I was automatically taken back to my first encounter with them. At first it was their peculiar and often even bizarre appearance that was so appealing. As I came to know more about them, I found out that this was in fact the result of a long process in which they developed adaptations to the conditions they have to cope with in their homelands.

I decided to make this the subject of my talk and called it “The survival of the fattest” (with apologies to Charles Darwin).

As the series of posts of which this is the first instalment, is based on and inspired by that talk, it seemed fitting to give it the same title.

Because succulents show such a bewildering variety in adaptations, it is not easy to recognise and understand the common elements. I have tried to arrange the material in this series of posts in such a way that at least some order is created out of chaos.

There is always more than one way to tell a story and the author has to choose which way to take. Each choice excludes a number of other possible ones. I can only hope that the choices I have made here do justice to the subject as well as appeal to the reader.

The main purpose of the pictures in these posts is to show what beauty can result from adversity; the text is meant to explain the mechanisms behind it all in understandable language. As I have lived in South Africa for a long time now and most of my pictures have been made there, it seemed logical and practical to approach the subject mainly from a South African perspective. This also makes sense because the dry parts of Southern Africa are among the richest succulent areas in the world; about half of all succulents occur here.

Other posts in this series:

What are succulents, actually?

Problems and solutions, part 1