(Another guest column by Theo Heijnsdijk)

* This is the name most often used for this plant, but if you want to follow the latest trend, you should call it C. perfoliata var. minor.

First of all, a quote from the Dutch illustrated weekly Floralia of 26 October 1933. The writer was G.D. Duursma, one of the founders of ‘Succulenta’ and a well-known figure in the Dutch succulent world.

Under the headline “Crassula falcata, a reluctant flowerer?” he wrote the following:

Crassula falcata, better known to the old florists as Rochea falcata, is a very classic succulent, which has disappeared almost completely from cultivation. In former days, half a century or more ago, every florist grew them and there were beautiful specimens to admire on all country estates. Nowadays, for the sake of completeness, they are still seen among succulent enthusiasts. They were acquired because, according to the books, they bloom so beautifully and so easily… ,but most people have noticed very little of that easy flowering. Is the plant to blame or is it the wrong treatment?

Crassula falcata hails from the area of the former Cape Province in South Africa. The plant, which has been known since about 1700, was described in 1798 by the German botanist Johann Christoph Wendland in the journal ‘Botanische Beobachtungen’. De Candolle gave the plant the name Rochea falcata in part 3 of his bilingual book ‘Plantarum Historia Succulentarum’ = ‘Histoire des plantes grasses’. He created the genus Rochea to accommodate the Crassulas with large tubular flowers. The genus name refers to the Swiss botanist Daniel de la Roche whose son François also was a botanist. Both died in Paris in 1813 of typhus (brought from Russia by Napoleon’s soldiers). To honour them both, De Candolle divided the genus into a section Daniela and a section Francisceana in 1828. In the aforementioned book by De Candolle, which appeared in episodes between 1799 and 1837, we also find an image (by Pierre Joseph Redouté) of Rochea falcata. I don’t think the resemblance is that strong. Much more beautiful is the image in Fragmenta botanica by Nicolaus Joseph Freiherr von Jacquin, which also appeared in episodes, published in the years 1800 – 1809. (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Plate from Fragmenta botanica by N.J. von Jacquin.

Here the plant is called Larochea falcata (genus name published in 1805 by the South African mycologist Christiaan Hendrik Persoon). Nowadays, the Rocheas are again simply included in the genus Crassula, whereas C. falcata is considered a variety of C. perfoliata. Perfoliata means ‘with the stems apparently growing through the leaf (or pair of united leaves)’ which obviously refers to the stem-encompassing leaf bases which give the impression that the stem grows through the leaves. We see this phenomenon even more clearly in C. perforata and related species.

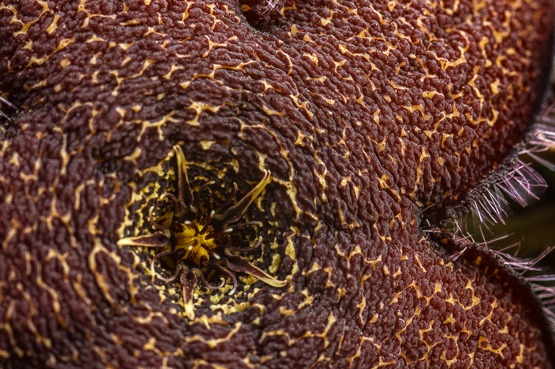

Despite its large leaf surface, C. falcata is excellently resistant to dehydration caused by sun and heat. This is a result of the structure of the epidermis. In the book “Pflanzenleben” by Kerner von Marilaun, published in 1887, extensive attention was already paid to this. In the book, there is an image with a cross-section and a view from above of the leaf surface (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Illustration from ‘Pflanzenleben’ by Kerner von Marilaun.

Fig. 2: Illustration from ‘Pflanzenleben’ by Kerner von Marilaun.

At 1, a cross-section approximately 600 times enlarged and at 2, a view from above, approximately 350 times enlarged. On the right, the armored cells are omitted so that the stomata become visible.

The accompanying text reads as follows (slightly abridged):

“The ordinary epidermis cells are small and only a little thickened on the outer wall. The cells that assemble the armor, on the other hand, are greatly enlarged. Their stem-shaped foot, which has been pushed like a wedge between the ordinary epidermis cells, is already relatively large; but the bladder-shaped swelling has dimensions that are 600 times the size of ordinary epidermis cells. All the vesicles are close together and, because of the pressure they exert on each other, have almost taken the form of a cube. Where, despite this, there would still be an opening, the bladders form bulges to the left and right, which interlock in such a way that a completely closed armor is created. The latter name is all the more justified here because the bladder-shaped swollen cells of Crassula falcata are hard as pebbles. Abundant silica is deposited in their cell wall and by annealing them one gets a real pebble skeleton, like Diatomaceae. It goes without saying that in the dry season such an armour is excellent protection against evaporation for the cells full of liquid that it covers.”

The armoured cells remind me very much of the basalt blocks with which dike slopes are reinforced.

As we have seen, back in 1933 G.D. Duursma observed that C. falcata was an antique plant that almost had disappeared from the collections. These days, it is all the way back. With its silver-grey to elephant-grey leaves, the plant fits perfectly into the modern interiors as well as the garden. For example, a few years ago nurseryman Smit from Sappemeer launched the ‘Eden collection’:

“This label guarantees the consumer strong plants that remind one of paradise.

The combination of exceptional shapes and colours with a unique name must give each plant a distinctive identity. No colorful overcrowded flower boxes, but a series of trendy, non-flowering plants in ornamental pots, bowls, or planters. All these plants can shine on the terrace table during the summer and in autumn you just take them inside. “

The paragraph overhead is a quotation from the grower’s promotional material. Part of the “Eden collection” is a bowl planted entirely with C. falcata. I have to admit, it looks beautiful.

Fig. 3: C. perfoliata var. falcata in the ‘Eden collection’.

Let’s return to the article “Crassula falcata, a reluctant bloomer?” from the ‘Floralia’ magazine. Of course, the word reluctant does not refer to the flowers as such, because it is particularly fascinating to see how the buds that are packed like a grey ball at first (fig. 4), unfold into an umbrella-like screen while gradually changing from yellow and orange-red (fig. 5) to fiery red (fig. 6). (There is also a white flowering variant).

Fig. 4: At first the buds are packed like a grey ball.

Fig. 4: At first the buds are packed like a grey ball.

Fig. 5. The umbel unfolds and the flower buds start colouring.

Fig. 6. The umbel’s colour changes from orange to fiery red.

Fig. 6. The umbel’s colour changes from orange to fiery red.

After the lines cited above, the article continues as follows:

“We know an old nurseryman in Friesland’s capital (note: Friesland is one of the Dutch provinces), someone who does not worry much about careful cultivation, and dozens of “Rocheas” bloom beautifully every summer for him. Other growers have tried to draw the secret from this Rochea specialist. But they did not find out the truth, because, when asked what he did to get such beautifully flowering Rocheas every year, the laconic answer was: “nothing!”.

And yet in this one word, the grower has revealed his entire secret. It’s incredible how casually, how barbaric almost, the Rocheas are treated here. ”

This is followed by an account of the especially ‘hard’ cultivation of these plants and the curbing of strong growth. The article ends as follows:

“The old grower whom we mentioned earlier on, knocks the plants out of the pot in spring and puts them in a sunny place, potting them again as soon as buds start appearing. ” In this case too, the plant is forced to flower due to a strong restraint from growing.

So the plants thrive most if they get a lot of sun and fresh air in summer and no more water than is necessary to prevent wrinkles. In winter, a cool but light place is recommended.

Propagation can be done by sowing and by taking stem or leaf cuttings, preferably with a little piece of stem. In sandy soil, the cuttings will root quickly.

Fig. 7: C. perfoliata var. falcata is easy to propagate from leaf cuttings.

For such a well-known plant, there are of course a number of ‘common’ names in addition to the botanical name. Apart from sickle leaf, we find the name propeller plant. English speakers also use the name ‘scarlet paintbrush’. G.D. Duursma affectionately calls it ” Cape beauty” in one of his books.

Over the years, it has been shown that C. falcata can be crossed with almost any other Crassula. This is all the more remarkable as there is an unlikely number of different growth forms in the genus. In his book ‘Crassula’, Gordon Rowley gives a diagram in which no less than 16 Crassulas are mentioned of which hybrids with C. falcata are known. In addition, there are a number of crosses that are not documented but in which C. falcata was probably also involved. In the beginning, people were looking for crosses with closely related species. This was done in 1898 with another Rochea (R. coccinea) and this hybrid was called C. x langleyensis. In 1936, C. exilis ssp. cooperi followed, which hybrid is now called C. x justi-corderoyi. In 1945, Dr. Meredith Morgan managed to realize a hybrid with the miniature (only about 1 cm tall) C. mesembryanthemopsis (fig. 8).

Fig. 8: C. mesembryanthemopsis, the father of C. ‘Morgan’s Beauty’.

Fig. 8: C. mesembryanthemopsis, the father of C. ‘Morgan’s Beauty’.

This resulted in “Morgan’s Beauty”. Probably everyone knows this plant. It looks like a C. falcata compressed in all dimensions and it blooms with a bouquet of fragrant pink flowers barely taller than the rosette (fig. 9).

Fig. 9: C. ‘Morgan’s Beauty’ (C. perfoliata var. falcata x C. mesembryanthemopsis).

Fig. 9: C. ‘Morgan’s Beauty’ (C. perfoliata var. falcata x C. mesembryanthemopsis).

I have found that this plant is almost irresistibly attractive especially to women. The only disadvantage is that the old flowers remain on top of the plant like an ugly plug. This property shares the plant with its father, as shown in figure 8.

Another well-known hybrid is ‘Buddha’s Temple’ (fig. 10) from 1959, a cross with C. pyramidalis.

Fig. 10: C. ‘Buddha’s Temple (C. perfoliata var. falcata x C. pyramidalis).

Fig. 10: C. ‘Buddha’s Temple (C. perfoliata var. falcata x C. pyramidalis).

We may also come across ‘Jade Necklace’ (fig. 11), a hybrid with C. rupestris var. marnieriana, also from 1959 and ‘Moonglow’ (fig. 12), a cross with C. deceptor from 1958.

Fig. 11: C. ‘Jade Necklace’ (C. perfoliata var. falcata x C. rupestris var. marnieriana).

Fig. 11: C. ‘Jade Necklace’ (C. perfoliata var. falcata x C. rupestris var. marnieriana).

Fig. 12 C. “Moonglow” (C. deceptor x C. perfoliata var. falcata)

Fig. 12 C. “Moonglow” (C. deceptor x C. perfoliata var. falcata)

And then there are crosses between these crosses, but we will leave them out of account here.

Literature:

Candolle, A.P. de and Redouté, P.J. (1799-1837): Plantarum Historia Succulentarum, vol. 3: t. 121

Jacquin, N.J. von (1809): Fragmenta botanica, figuris coloratis illustrata, t. 82

Kerner von Marilaun, A. (1902): Het leven der planten, after the 2nd edition, tyranslated by Dr. Vitus Bruinsma

Laren, A. J. van (1932): Vetplanten, Verkade factories N.V., Zaandam

Rowley, G. (2003): Crassula, Cactus & Co.

Wendland, J.C. (1798): Botanische Beobachtungen, 44

Originally published in Succulenta 92 (2013) p. 3-11. Translated from the Dutch by F.N.