EXCESS OF ENERGY

In general, organisms can only survive if the quantities of water and energy entering are at least as big as those leaving them.

Succulent plants usually receive too much energy (solar radiation, wind) and too little water, which makes their balancing act even more complicated.

Radiation

In many arid areas the light intensity is usually high – often 2-2.5 times as much as in more temperate climates – and because there are few clouds, there are also more hours of sunshine.

When the radiation becomes too high it may damage the plants’ chlorophyll or overheat their tissues.

Succulents have developed a variety of means to reduce these dangers (upright stems or leaves, hairy or wax-covered skin, covers of spines etc.). Many columnar succulents bend in the direction of the sun and in leaf succulents the new and vulnerable leaves often grow upright at first, becoming more horizontal over time.

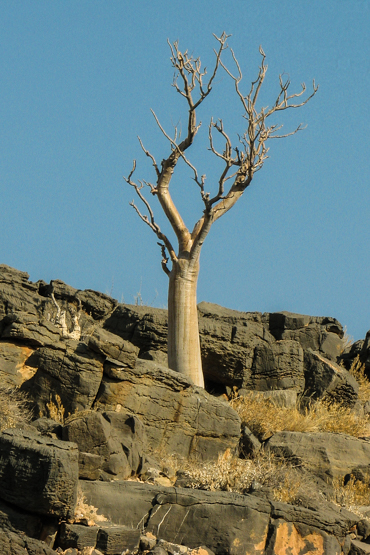

Another way to avoid the dangers of high radiation is hiding under shrubs, in rock crevices etc. This also helps against strong winds and browsing animals.

Temperatures

As a result of the large amounts of radiation, temperatures are often high during the day. In many cases there are great differences between day and night temperatures (often more than 50°C) as well as a great variation over the year.

The temperatures of soil surface may even reach 70°C.

Because the roots of succulents are usually near the surface, this is bound to cause problems. Under rocks it is much cooler, so many roots are found there. No wonder many succulents seek shelter near or in between rocks.

Whereas reduction in size is a good strategy for coping with lack of water, miniature succulents (by definition growing near the soil surface) will be severely affected by these high temperatures. The same applies to young seedlings. Plants in general may get rid of excessive heat by means of transpiration, convection or long-wave emission, but often these options are not available to succulents:

– using transpiration to lower body temperature would lead to unaffordable water losses

– their low surface area-to-volume ratio reduces the boundary layer where convection can take place as well as the area from which long-wave radiation may be emitted.

Wind

Wind is usually present and often hot and strong. The continuous replacement of air around the plants has a desiccating effect so that water loss can be extreme.

In many arid regions sandstorms are a regular occurrence, transporting not only dust and sand but often also small stones, damaging plants and remove hairs or wax cover through abrasion in the process. Seedlings are especially vulnerable in this respect.

PREDATORS

Because of their juicy contents, succulents are attractive to herbivores, but many of them are unpalatable. This may be because they are very bitter (Aloes), contain a sour, salty sap (Augea capensis, Mesembryanthemum crystallinum, M. guerichianum) or a milky latex (Euphorbia ssp.), or even because they are poisonous (Cotyledon, Euphorbia, Sarcostemma, Tylecodon).

For other posts in this series click here.