By Theo Heijnsdijk

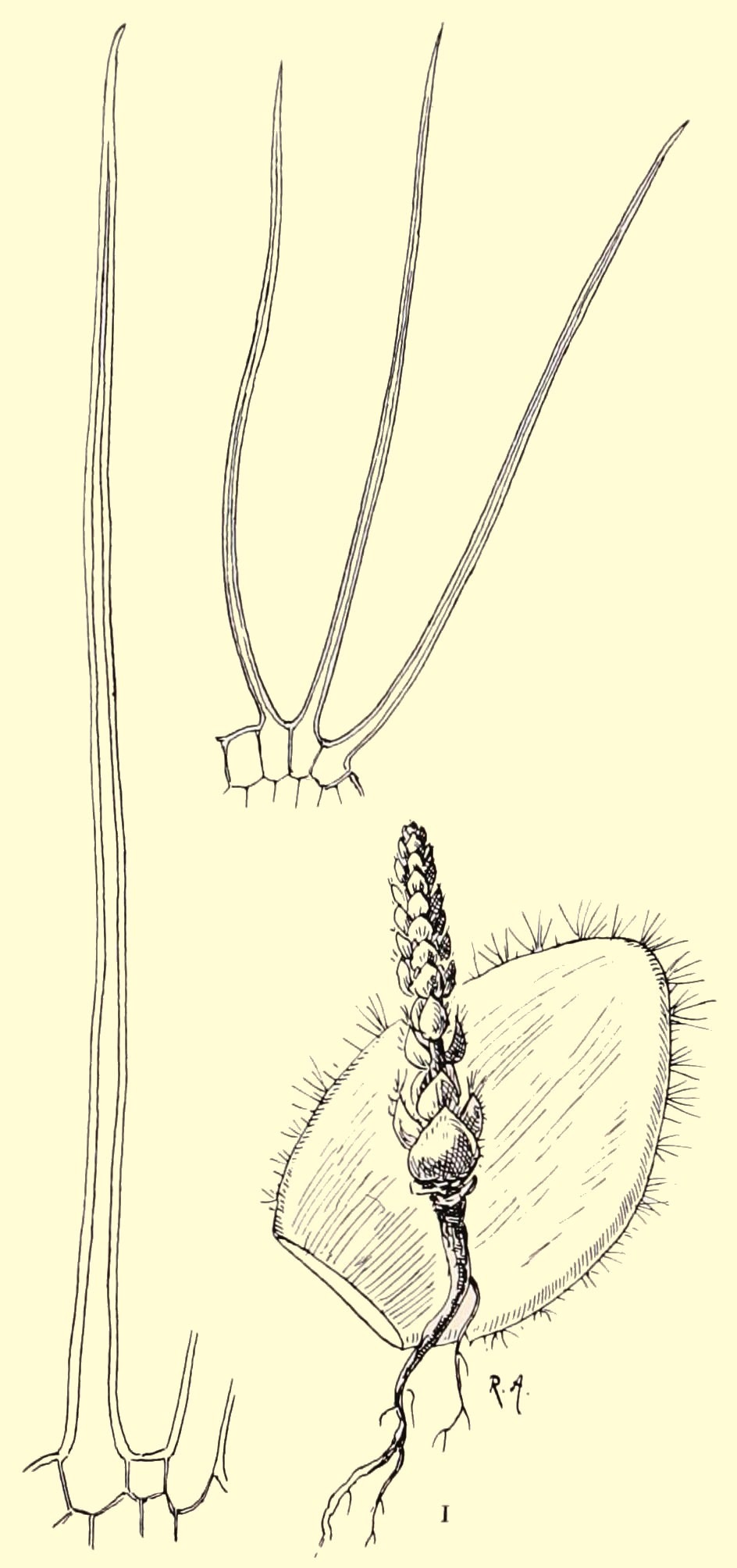

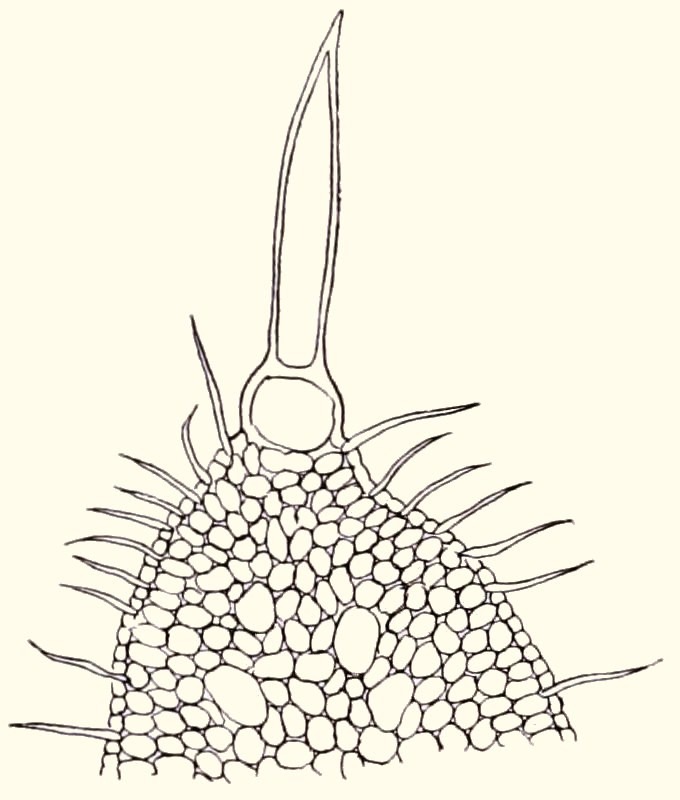

C. barbata is among the 28 new South African Crassula species described by Carl Thunberg in 1778. In nature it occurs on rocky slopes in quite a large area including, among others, the Great Karoo and the Little Karoo. Characteristic for the species are the up to 5 millimeter long hairs on the leaf margins which give the impression of entangled eyelashes (fig. 1) or a beard – as the the botanical name implies (barbata = with a beard). At the tips of the leaves the hairs are often gathered in little tufts (fig. 2). Apart from this, the leaves are completely hairless. In nature, the plantlets often look like little fluffy globes. See fig. 3, a picture made by Coby Keizer in November 2008 at a spot about 40 kms west northwest of Matjiesfontein where a lot of interesting little succulents grow together.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

In the guest column on CRASSULA PYRAMIDALIS *, I mentioned the experiments that Rudolph Marloth carried out early last century to assess water absorption by Crassulas through the leaves and hairs. A plant of C. barbata gained 5.2% in weight in one night by absorbing dew. Marloth also looked at what happens when you apply a small drop of water to the end of a hair on a wilting leaf. Before long, the hair swells and stands upright and gradually the leaf regains its turgor. In Crassula tomentosa (fig. 4), with its row of thick hairs, this works even better. Marloth took a leaf from it and dipped the hairy edge in the water. After 12 hours, the weight had increased from 14.45 to 16.05 gram, an increase of no less than 11%.

fig. 5

fig. 5 fig. 6

fig. 6

C. barbata is a slow grower. It takes a few years until the heart of the rosette opens and the beginning of the flower stem becomes visible (in the Netherlands usually at the end of November). At this stage, the flower stem looks like a C. pyramidalis plantlet (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 Fig. 7 The stem grows rapidly (fig. 8 and fig. 9) and after a few weeks the maximum height (up to 30 cm) is reached.

Fig. 7 Fig. 7 The stem grows rapidly (fig. 8 and fig. 9) and after a few weeks the maximum height (up to 30 cm) is reached.

f

f

Fig. 8

Fig. 10

Pink shades also occur . Fig. 11

Fig. 11

The flowers emit a pleasant, sweet smell.

There is only one known variant of C. barbata: ssp. broomii, also known as an independent species: C. broomii. It grows in the vicinity of Victoria West (North Cape) in the mountains and is distinguished from the type plant mainly because the hairs are considerably shorter, up to only 1 mm. For plantlovers this makes it not so interesting, because it is precisely the hairs that make the plant so attractive. We therefore hardly ever encounter this variety in collections.

There are also hybrids of C. barbata, but they are not common in culture. In an article in Succulenta (1980), B.K. Boom mentions a cross with C. orbicularis cv. ʽRosula’ and also shows a photo. Rowley mentions a cv. “Roger Jones” as being “C. barbata x ? orbicularis”, but does not give an image.

Gordon Rowley, in his book ‘Crassula’, considers C. barbata a joy to see in its natural habitat but usually a disappointment in cultivation. Instead of remaining compact, the plants grow into elongated loose rosettes and after flowering the plant dies. But he also made this kind of statement about C. columnaris and C. pyramidalis. My experience is that it is not as bad, as long as you are economical with water. Watch out for total dehydration in summer and give the plant the lightest spot you can find in winter.

Also, the plant does not always die after flowering. For example, I had a plant that bloomed in the winter of 2011-2012. As the rosette died off, 5 new shoots formed at the base of this plant. At the moment, at the beginning of December 2013, a flowering stem rises above the rosette in all 5 of them. So, you can enjoy such a plant for years.

Literature:

Boom, B.K. (1980). De Crassulas van onze collecties 6 and 7, Succulenta 59 (1): 120.

Laren, van, A,J. (1932). Vetplanten, Verkade fabrieken N.V., Zaandam.

Marloth, R. (1908). Das Kapland, Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition auf dem Dampfer “VaIdivia” 1898-1899, bd.2, t.3.

Noltee, F. (2008). Succulenten van de Karoo, een bezoek aan Perdekraal, Succulenta 87 (4): 170 and Succulenta 87 (5): 215.

Rowley, G. (2003). Crassula, Cactus & Co.

Thunberg C.P. (1778). Nova acta physico-medica Academiae Caesareae Leopoldino-Carolinae Naturae Curiosorum 6: 328-341.

Originally published in Succulenta 93 (4) 2014. Translated from Dutch by Frans Noltee.