Succulents are mainly found in areas where dry periods are regularly followed by a rainy season, so that the plants can fill their storage organs for the next dry season. This means they are relatively rare in regions where precipitation is very unpredictable or the dry periods are often longer than a year.

In other words, although we tend to think of succulents as typical desert-dwellers, in fact they rarely occur in extremely arid areas. (An area is usually called arid when it receives 70–150 mm precipitation per year and semi-arid when the figures are 150–400 mm per year).

In some coastal deserts with extremely low rainfall, such as the Atacama in South America and the Namib in southern Africa, succulents can survive and even thrive because of the runoff from nightly fog. To give you some idea of the importance of this phenomenon: for Swakopmund in Namibia, fog is recorded on 150 days per year.

The presence of succulents is limited by low temperatures, especially when these occur in the growing period. Several species though can stand temperatures as low as -10°C for a short while.

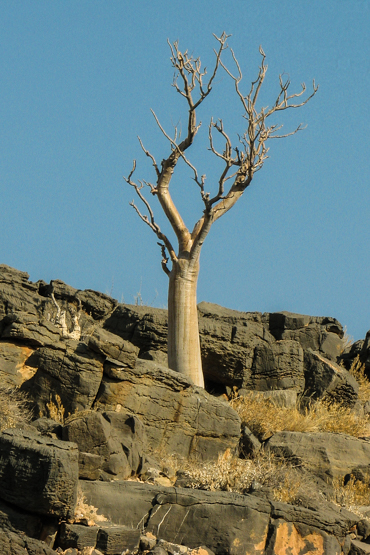

Factors such as soil type, drainage, wind speed, aspect, relief etc. play a role too. As a result of all this, succulent plants are not only found in more or less extended dry zones, but also in smaller pockets of dryness in environments that are generally much wetter (think of places like dunes, inselbergs, rocky outcrops etc.)

There are 2 main distribution centres for succulents:

Firstly we have the dry areas of the new world: Arizona, Mexico, central and South America. Here we mainly find cacti, but there also many other succulents.

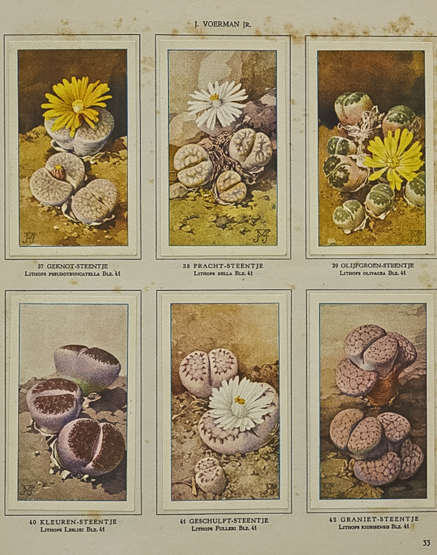

The second centre is formed by the dry regions of Africa, including the Canary islands, Madagascar and Socotra, as well as the southern part of the Arabian peninsula. Far richer than any other region here is the Succulent Karoo, the winter-rainfall area of southern Africa, which includes one of the mist deserts mentioned above.

Europe, Asia and Australia are home to relatively very few succulents.

In conjunction with this post a new photo gallery is published with pictures of

— habitats where succulents are known to occur and of

— succulents showing much more of their natural environment than usually in my pictures.

Go to gallery.