Succulent organs filled with water are quite heavy. In miniature succulents most of the body weight is near the ground, so that there is little or no need to build and maintain a strong support system. Because they are so compact, they are also far less exposed to external influences than other plants.

Plants like this Conophytum praesectum from near Pofadder are small enough to benefit from shade cast by pebbles

The fact that a great part of the plant is near to the soil has another -and rather unexpected- advantage. In the areas where succulents grow, wind is usually present and is often hot and strong. The continuous replacement of air around the plants has a dehydrating effect, so that evaporation can be extreme. Apart from this, the wind transports sand and dust, causing sand abrasion, which may damage the plants (especially seedlings) and remove hairs or wax cover.

Because of surface roughness, wind speed is zero at ground level, and wind becomes stronger with increasing height above the ground. It follows that the lower the plant, the less likely it will be to suffer from wind damage.

A drawback of being small is that smaller leaves and stems have a larger surface-area-to-volume ratio than large ones. As a result, their transpiration is relatively higher and they are more prone to heat stress. The fact that dwarf succulents have more or less spherical leaves or stems, helps to alleviate the problem. With regard to minimising evaporation, a sphere is the ideal shape, as it combines the minimum surface area with the maximum internal volume. (The surface area of a flat leaf is about 40 times bigger than that of a perfect globe with the same contents).

In the rare Muiria hortenseae from the southern Little Karoo, the two leaves making up each body are fused almost completely, so that the flowers have to force their way out

In some cases, pairs of leaves have grown into one, so that each pair resembles a little globe. Densely packed leaves or stems can attain similar results.

In Crassula pyramidalis the leaves fit so densely together, that it first sight the plant looks like a stem succulent rather than a leaf succulent

Water loss from the surface of the plant can further be minimised by (the plant) hiding underground. In dry periods, the plants are often completely hidden in the soil, covered with the sand and dust blown over them. Only when the bodies fill out at the beginning of the rainy period do they appear above ground again.

Experiments have shown that in Lithops the rate of water loss is about a fifth lower in plants that are embedded in the soil than in those totally exposed.

In addition, the daily variation of temperature in the leaves is reduced. This is important during the hottest part of the day, when the parts of the plant that are furthest away from the soil surface, stay cooler than those nearer the ground.

Hiding underground also has its disadvantages. Because less surface area is available, photosynthesis is much reduced, so growth is slowed down.

The famous window plants have found a way to reduce this problem. These plants occur almost exclusively in the dry winter rainfall areas of southern Africa and are found in just a few families- most commonly the vygies (Aizoaceae, several genera). Other examples are Haworthia and Bulbine.

Haworthia truncata has a limited distribution area around Calitzdorp and Oudtshoorn. It is one of a number of Haworthias with windows

A perfect specimen of waterglasie (Bulbine mesembryanthoides)

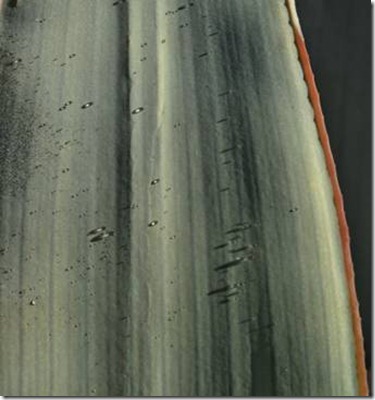

The classic example is Fenestraria rhopalophylla: The plants are practically stem less and have club-shaped leaves with a translucent area on top.

As only a small part of the leaves is exposed to light, photosynthesis would normally be seriously hampered. The window at the top however, combined with translucent water-storage cells deeper inside the leaf, makes it possible for light to penetrate into the leaf and reach the inside of its mantle. Here, (there) are cells that contain chlorophyll and make photosynthesis possible.

The plants grow in the mist zone on the coast of northern South Africa and southern Namibia where the leaves are drawn into the ground by thick contractile roots. Usually the plants grow in deep sand, but sometimes they are found in pockets above dolomite rocks. Although the plants are only a few centimeters across, the root system may cover up to 2 metres. The mat of fine roots just underneath the surface is able to absorb the condensation of the moisture brought in by the sea fog, which is the main source of water for these plants.

The leaves are usually flush with the sand so that they do not suffer from the strong winds that blow almost daily.

This F. rhopalophylla ssp. aurantiaca was photographed south of Port Nolloth, in close proximity to the sea

The so-called stone plants – among the smallest flowering plants in the world- have followed a slightly different route. They have very thick leaves, often with dark green dots in their leaf tops. These dots contain no pigment and may be either large single cells or a group of smaller ones. They lie just below the epidermis and serve as micro windows, which may take up to over 40% of the leaf surface. In winter, when the sunlight is weak, the non-pigmented zones help it to penetrate into the leaves.

Lithops localis near Prince Albert, showing its many micro windows

A peculiar adaptation is shown by many members of the mesemb family (Aizoaceae), especially the dwarf ones, which are able to recycle water from old leaves to new ones.

This phenomenon was already discussed in an earlier post (Water recycling in succulents, 4th Dec. 2012), so please have a look there if you are interested.

In this article, I have tried to highlight some of the intriguing adaptations miniature succulents deploy in order to survive. Of course, these are only a few of the techniques and strategies they have in common with other succulents. But that is another story, for another day.

***

The original version of this article appeared in the most recent issue of Veld & Flora (March 2013). If you are interested in the immensely rich flora of South Africa, it is well worth visiting their website: www.botanicalsociety.org.za.

***

Since I wrote the article I acquired a new piece of software (Inspiration) which allows the user to make mind maps, concept maps, flow charts etc. in a very intuitive and easy way. I had tried out similar programs before, but never liked the results, nor the way they worked. To my mind, this program scores well on both points.

As I am currently working on a book on how succulents survive in the wild, I thought it might be helpful to use a diagram such as the one below, to make complicated processes and relations a bit clearer.

It would be great if readers would have a critical look at this diagram and tell me if it works for them. Many thanks in advance!