Because they may form large clumps to over a meter in diameter, plants of this species are often quite conspicuous in the field. They occur widespread in the Great Karoo and from Calitzdorp to the Eastern Cape and into the Free State, usually among bushes on lower stony slopes or under trees on flats.

The stems are up to 30 cm long. As the name implies, the flowers are often quite big too (mostly 8-15 cm, but sometimes up to 22 cm in diameter); they are usually silky hairy and appear mainly from March through May. The buds are rounded, which is typical for this variety (see last picture, showing a plant in cultivation).

The first 3 pictures were made near the Calitzdorp Dam, 6 April 2010.

Tag: Great Karoo

Antimima pygmaea (part 2 of 2)

It may be of interest to see what Prof. Schwantes in his magnum opus Flowering Stones and Mid-Day Flowers (1957) has to say about this “most remarkable and interesting species”: “This forms annually only two pairs of leaves to each growth which, however, are differently shaped. This phenomenon is called dimorphism of the leaf. The pair of leaves that appears at the beginning of the rainy season from out of the dry sheath is united into a long sheath at the base but developed normally above into widely separated, yawning, broad leaf tips. This pair of leaves with its comparatively broad surfaces that catch the light and absorb carbon dioxide as nourishment, provides food during the growth period. When the end of this period approaches there pushes out of the channel formed through the uniting of these normally developed leaves a peculiar, elongated, cylindrical structure which consists of two leaves joined right up to the tip. The very short ends are separated only by a slit, which shows that the growth actually consists of two thick leaves. Growths which consist of such closely united leaves are called plant bodies (corpusculum). The object of this close union can only be to reduce the evaporating surface as much as possible and to protect the young growth within from being dried up. The plant’s struggle to make the leaf pair as nearly spherical as possible is here obvious; as is known, the sphere is the form with the smallest surface area. Within these leaf pairs or plant bodies the next pair develops, which once more is less completely united. Inside the body a channel running its whole length remains open; the slowly developing leaf pair is fitted into this and draws from the plant body food and water until it has dried up to a parchment-like skin which completely surrounds the young pair so that not even the tip projects. In this condition the growth, well protected by the skin, lives through the dry period and when the rains begin the deeply buried pair of leaves quickly emerges from the skin surrounding it. In Ruschia pygmaea quite distinct leaf pairs are produced for the dry and for the rainy seasons, one of which has a large surface for assimilation, while the other serves for the protection of the resting pair.”

Antimima pygmaea (part 1 of 2)

There are not many plants that look better or more interesting in the resting state than during active growth, but this species is certainly one of them.

The plants form low, densely branched mats to 15 cm in diameter.

The leaf pairs are dimorphic. One pair is almost fused almost completely, to 5 mm tall and 3 mm wide, developing into a conical body which turns into a dry sheath protecting the subsequent leaf pair during the dry period. These white bodies become slashed with time and are typical for the species.

The plants occur on shaly slopes in a smallish area between Worcester and Laingsburg.

Irrespective of the statement in the first sentence of this post, the plants are quite cute when in flower. The flowers are up to 18 mm across and appear in winter (July-August).

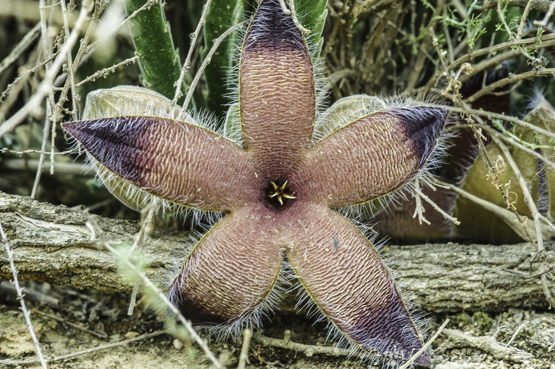

Huernia pillansii (part 1 of 2)

With its almost furry stems this species is easy to identify, even without flowers.

Only Stapelianthus pilosus from Madagascar is somewhat similar.

The stems are normally 1.5-6 cm long, but may reach as much as 18 cm; they usually have 10-16 spiral or vertical series of tubercles ending in long hairs. These hairs shade the stems and thereby reduce water loss.

The flowers have an unusual appearance too and appear in spring and summer (Dec.-May).

The plants are found sporadically on stony slopes and clayey flats from Montagu eastwards to Steytlerville in the Eastern Cape and in the Great Karoo from Matjiesfontein to Beaufort West. They occur mostly in the shade of low bushes.

Conophytum minimum (part 3 of 3)

Conophytum minimum (part 3 of 3)

Conophytum minimum (part 2 of 3)

Conophytum minimum (part 1 of 3)

When Adrian Haworth described Conophytum minimum in 1795, it was the smallest known member of the genus Mesembryanthemum (as it was back then). Hence the specific epithet.

It is a member of the section Conophytum – “The original cones and dumplings” as Steven Hammer calls them. As in other members of this section, plants of C. minimum may vary from quite plain and dull to exquisitely marked. This variability has given rise to a long list of synonyms (26 to be exact).

The plants form rather loose mats or compact domes.

The individual bodies are conical to cylindrical, 8-15 (sometimes up to 20) mm long and 10 mm thick, elliptical in outline and with their tops usually truncate (as if cut off). They range in colour from pale green to greyish green and the tops are mottled in various degrees with dark lines and spots.

The flowers are white, pale yellow or pale pink and strongly scented. They appear in autumn (May, June). Although they are described as nocturnal, on cold days they are often open in the morning (up to 10 or 11 am) or late afternoon.

When you want to see the plants in the wild, your best chances are in the Matjiesfontein, Laingsburg, Witteberg area, where they are often locally abundant on shale, sandstone or quartzitic rocks among lichens, often finding shelter in crevices.

The photos in this post and the following two ones, are arranged chronologically so as to give you an idea what the plants look like in different times of the year.

Picture taken 29 Jan. 2012

Pictures taken 6 May 2009, around 5.40 PM

Senecio cotyledonis (2)

Senecio cotyledonis (1)

When the Swiss botanist Augustin de Candolle described this species in 1838, he apparently saw a likeness to a Cotyledon. But when I ran through the mental pictures of Cotyledons that I know, I wondered what resemblance he could have had in mind. So, some detective work was called for.

Did de Candolle compare his new species to a plant that at that moment was incorporated in Cotyledon, but now belongs in another genus? That is certainly a possibility, as no less than 471 plant names have been associated with the genus at some stage.

On the other hand, looking through “Cotyledon and Tylecodon” by Van Jaarsveld and Koutnik, it struck me that some narrow-leaved forms of C. orbiculata could well have been the inspiration for de Candolle’s name. Let’s not forget that he probably knew many plants from descriptions or at best from black and white drawings, rather than from live material. In the book I just mentioned, there are a few reproduction of old illustrations. One dates back to 1701 and represents Cotyledon africana frutescens, folio longo & angusto…. ( the shrubby Cotyledon from Africa, with long, narrow leaves), which is now known as C. orbiculata var. spuria. This picture may well have spurred (pun intended) the author to use his epithet.

Well, enough of historical speculation, let’s move to present-day reality.

S. cotyledonis is a shrub of up to 1 m tall, with thickish stems and succulent triangular to almost round leaves up to 5 cm long and about 3 mm wide. The leaves give off an unpleasant smell when damaged, which is why it is called stinkbos in Afrikaans.

The plants flower in spring. They are widespread from Namibia to the eastern part of the Little Karoo. Usually they are found on dry stony slopes, but sometimes they are abundant in clayey soils.

To be continued.