Introduction by Frans Noltee

Some ten years ago, the Dutch journal Succulenta featured the first of what was to become a long series of articles on well-known cacti and other succulents in cultivation, written by Theo Heijnsdijk. Recently the author approached me to ask if I might be able to supply him with a habitat photo for an article in this series. That request caused me to have a new look at the articles he had published and this, in turn, convinced me that some of them would fit into my blog and indeed make a worthy addition to it.

When I suggested this to Theo, he was very enthusiastic about it and as a result, I am now grateful and proud to publish the first of what will hopefully become a series of articles on African succulents in cultivation.

*********************************************************************

Ceropegia stapeliiformis was sent to Europe in 1826 and described in 1827 by the English botanist Adrian Haworth. The name of the plant (often wrongly spelled as stapeliaeformis), obviously refers to the resemblance of the non-flowering stems to those of a Stapelia.

When not in flower, C. stapeliiformis is not particularly attractive. The stems are about as thick as a finger and crawling, climbing, or winding; usually, they are leafless with rudiments of leaf stalks. They are greyish brown (to olive green in cultivation), often with stripes or dots.

But the blooms make up for it. When C. stapeliiformis is preparing to flower, it will form tendrils, i.e. long thin stems (up to 1.5 m), which like to wind themselves around a stick or something similar (see picture 1). In nature, these flowering stems swing up in bushes, probably to make the flowers easier to find and more accessible to pollinators (small flies).

Several flowers develop in succession on a flower stem (peduncle); they form a hairless tube at the bottom which becomes funnel-shaped higher up and ends in five narrow outward-curved petals. These petals are hairless on the outside and covered with white hairs on the inside. Their colour varies from reddish-brown (picture 2) to green with white (picture 3). The total length of a flower is about 6 cm.

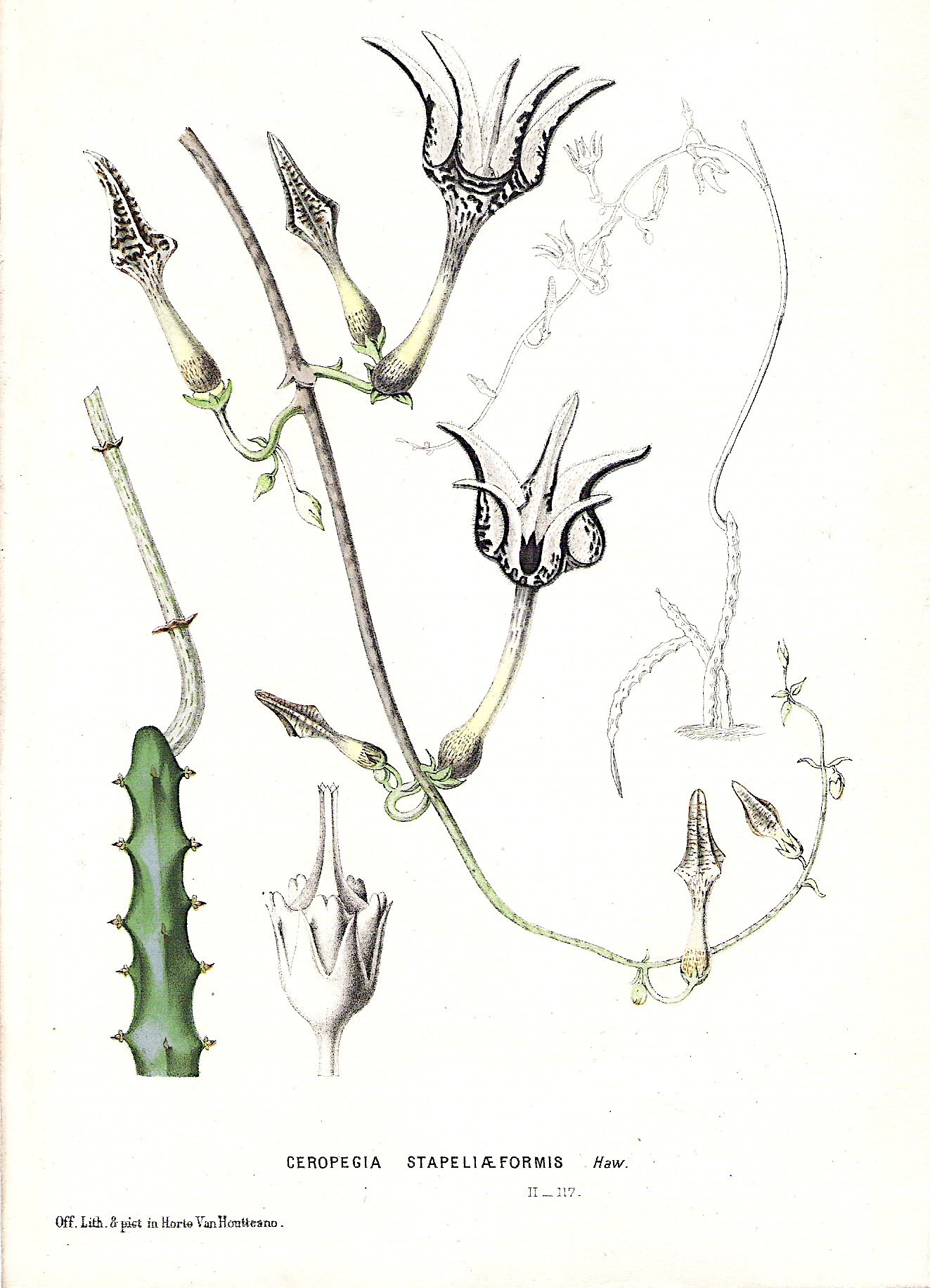

The oldest image I could find was in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine of 1837, plate 3567. A particularly beautiful image can be found in year 2 of the horticultural magazine ‘Flore des serres et des jardins de l’Europe’ (see picture 4). This magazine was published between 1845 and 1883 and consisted of 23 volumes with more than 2000 coloured plates. It was founded by the Belgian horticulturalist and botanist Louis Benoit van Houtte (1810-1876). From 1836 to 1838 he was director of the National Botanic Garden of Belgium in Brussels. Later he started a nursery/ floristry. Around 1870 the nursery occupied 14 hectares and there were no less than 50 greenhouses. From 1845 he sent collectors to Central and South America. They brought back rare plants such as orchids. He was also the first on the European mainland to have the giant water lily (Victoria amazonica) in cultivation and to get it into bloom.

C. stapeliiformis occurs in the Eastern Cape, south of the 31st parallel, where it usually grows in the shelter of scrub.

C. serpentina (described in 1949) nowadays is considered a subspecies of C. stapeliiformis.

So, we have C. stapeliiformis subsp. stapeliiformis (the original species) and C. stapeliiformis subsp. serpentina (= like a snake). The latter occurs north of the 29th parallel, in the north-east of South Africa, and in Eswatini (the former Swaziland).

Many publications mention the curious tendency of the stems to suddenly grow down, drill into the ground and reappear at some distance. Let’s have a look at what Chr. de Ringh wrote in the Dutch magazine ‘Succulenta’ in December 1933:

Gradually, an offshoot developed at the bottom of the cutting. It lifted itself above the ground for a while and then drilled its tip into the soil. I let it do its thing and within a short time, it had gone deep down. One day it reappeared above ground some 20 cm away and then quickly grew to a big affair of about a metre long. Such a stem prefers to turn around a stick and then go up like a bean around a stake. Although my patience had been tested for a long time, I was finally rewarded as well as surprised when buds appeared.

The flowering period in cultivation is from April to October (in nature October to March) and a large plant may produce hundreds of flowers in this time.

As far as cultivation is concerned: use well-drained soil (with e.g. 1/3 coarse sand and an addition of clay); in summer ample and in winter little or no water. Beware of stagnant moisture, because that will cause the plant to rot quickly. Rotting also occurs if temperatures are too low and/or humidity too high in winter. Temperatures should not be below 5 to 8° C.

Propagation is possible by cuttings or seed. Sowing is fun and not difficult. The seeds are flat and fairly large and germinate within a few days. In the third year, seedlings may already flower.

Unfortunately, we rarely find the species in the seed lists. This must have something to do with the complicated pollination mechanism of the family to which the Ceropegias belong. For those interested (and able to read Dutch), I can recommend the description by Arie de Graaf in ‘Succulenta’ of February 1977. After a successful pollination, the bipartite fruit develops. It resembles two pods that grow in a V-shape on a common stalk. The length of a pod is about 10 cm. When it matures, such a pod tears open (picture 5) and then unrolls. The seeds are now ready to be on their way. Like the seeds of a Senecio (or of a dandelion and such), they are equipped with a tuft of white hairs (picture 6). This way they can be taken by the wind and land at some distance from the mother plant. The tuft of hairs will disappear somewhat later. The seeds germinate after a few days and the plantlets will grow fast (picture 7).

Usually, we will have to use cuttings for propagation. The best time for this is spring. Because the cuttings often bleed, it is advisable to dip the cut surface in charcoal, ash, or something like that first. Of course, one should allow the cuttings to dry first (about ten days), before sticking them into the ground. It will take about a month before roots appear.

Literature:

Haworth, A. (1827). Description of new succulent plants, The philosophical magazine or annals of chemistry, mathematics, astronomy, natural history and general science: 121.

Lemaire, C. (1846). Flore des serres et des jardins de l’Europe 2 (6): t4.

Noltee, F and H. van Donkelaar (1965). Ceropegia stapeliaeformis, Succulenta 44 (5): 70-72.

Ringh, Chr. De (1933). Ceropegia stapeliiformis, Succulenta 15 (12): 217-219.

Sims, J. (1837). Ceropegia stapeliiformis, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 64: t 3567.

Soldt Sr., O. van (1977). Het lelijke eendje dat een wondermooie zwaan werd. Succulenta 56(2): 47-50.

Originally published in Succulenta 89 (3) 2010. Translated from the Dutch by FN.

Author’s email: th.heijnsdijk@gmail.com

Fig. 2: A flowering C. stapeliiformis lives up to the name lantern plant

Fig. 3. C. stapeliiformis flower with green petals

Fig. 5 Opening fruit

Fig. 6. Open fruit with seeds

Thank you for the translation Frans, it takes time to do, but helps to share the information to a wider audience. I’m looking forward to more of Theo’s contributions. Lovely photos too!

Hello Retha,

Although it’s quite a bit of work, it is fun to do. There’s more in the pipeline!

Marvelous article and pictures-what a great collaboration. Thanks for sharing this.

Thank you very much for your kind words. Glad you liked the post.