Kalanchoe delagoensis is sometimes regarded in quite different ways. Those who Google Kalanchoe tubiflora (the name under which the plant is better known), will find both “How to grow Kalanchoe tubiflora” and “How to kill Kalanchoe tubiflora”. The latter is not intended for the many plant lovers who consider this plant to be weeds in their greenhouses, but for use in the many areas of the world where the plant has started to grow and poses a threat to livestock because of its toxicity. More on this later in this article.

There are also differences of opinion about what is the correct name for this plant.

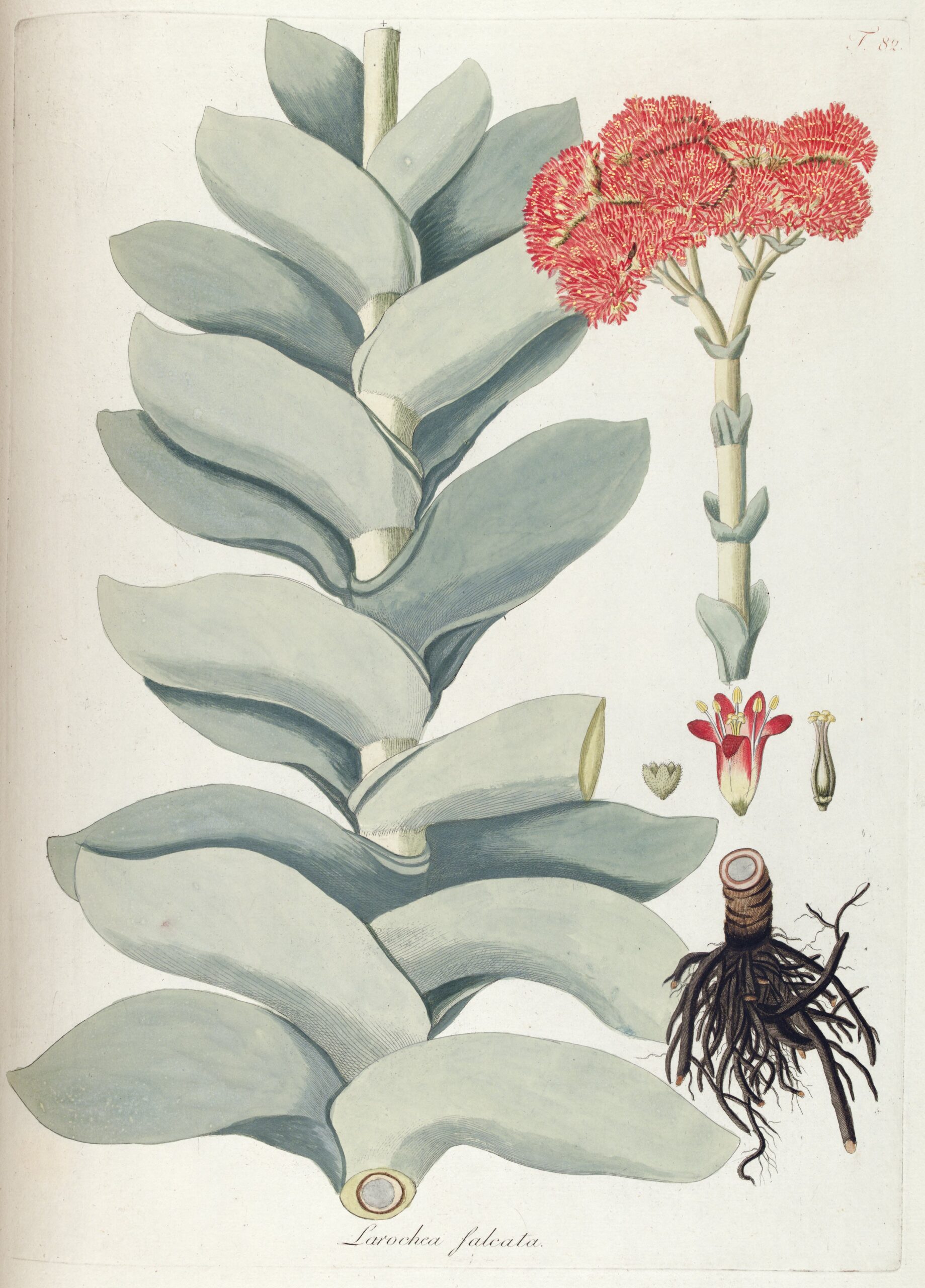

For starters, Bryophyllum is very often chosen as the genus name. This name aptly reflects the property of the plants in question to produce miniature plants on the margin of the leaves that detach easily and then quickly develop into powerfully growing plants. Others choose to consider Bryophyllum as a section in the genus Kalanchoe.

The origin of the name of the genus Kalanchoe (described by the French botanist Michel Adanson in 1783) is not at all clear. Maybe it’s a phonetic transcription of the Chinese jia lan cai shu (I also came across kalan chau huy) and this would have been corrupted to Kalanchoe. Jia lan cai shu is said to be the name of a species occurring in China, possibly K. ceratophylla or K. spathulata. Searching the internet, I found out that nowadays the Chinese name for Kalanchoe is also Jia lan cai shu (see Flora of China 8: 204–205. 2001), so I wonder if it is not the other way around, to wit that the Chinese name is a corruption of the botanical name.

Other sources refer to the names from Sanskrit kalańka-, “stain” or ” rust”, and chāyā, “clear” which would refer to the leaves of the Indian species K. laciniata.

I also read somewhere that kalan chau huy would mean “that which falls and grows” which would be a perfect description of the plants of the Bryophyllum section. But this seems like “wishful thinking.” All species of the Bryophyllum section occur naturally exclusively in Madagascar which is very far away from China.

With regard to the species name, it should first be noted that “delagoensis” refers to Delagoa Bay (now Maputo Bay) near the capital Maputo of Mozambique (until 1975, when Mozambique became independent from Portugal, called Lourenço Marques). A surprising name for a plant that originates from Madagascar which is located some 1200 km from Delagoa. In order to understand the discussion properly, it is necessary to look into history.

It started in February 1822, when the British royal ship, the “Leven” (equipped with 28 cannons) under the command of Captain William Fitzwilliam Owen, together with the accompanying ship the Barracouta (10 cannons), embarked on a 5-year expedition to map the entire east coast of Africa as well as Madagascar and other islands in the area. The entire expedition is described in detail in a report published in 1833 (2 books, together almost 850 pages) by Captain Owen. Two years later, a similar but even more extensive report, by Second Lieutenant Thomas Boteler (2 books, 900 pages) was published. Onboard the Leven was the young botanist John Forbes, dispatched by the British Horticultural Society. Via Lisbon, Madeira, Tenerife, the Cape Verde Islands, Trinidad, Rio de Janeiro, and the Cape of Good Hope, the ship reached Delagoa Bay for the first time at the end of September of the same year. In Rio de Janeiro alone, the tireless Forbes had already collected more than 300 plants for his herbarium, in addition to numerous seeds and rhizomes.

In later years Delagoa became a kind of base from which all kinds of expeditions were undertaken. It was regularly reported that the many mosquitoes kept the people who were ashore awake. More and more people also became ill. There was no knowledge of malaria and the only treatment known against the mysterious fever was bloodletting.

When no less than 19 of the 60 crew members had died at the beginning of December 1822, Captain Owen decided to head for Madagascar. On December 5, the ship departed and on December 21 they arrived at St. Mary’s Island (Île Sainte-Marie) on the eastern side of Madagascar. On January 8, the Leven left for the much more northerly Comoros, and sailing along the coast of Mozambique they were back in Delagoa Bay at the beginning of March 1823. During a stay in Cape Town in May 1823, Lieutenant Browne, botanist Forbes, and assistant physician Kilpatrick volunteered for an expedition upstream from the mouth of the Zambezi River. The intention was to go upstream for some 600 miles and then try to cross to the Cape of Good Hope. With a large canoe and 2 ‘black’ helpers, they entered the estuary on July 23. Forbes fell ill on August 3. Several bloodlettings were to no avail and on August 16 he died, aged 25. Soon after, both of his comrades fell ill too. Browne died on September 5 and Kilpatrick on October 28. The two helpers were also sick but survived.

Captain Owen, meanwhile, was already at Delagoa, where he raised the British flag on the south coast in September. At the bay 4 rivers flow into the sea and he realized the importance of this large natural harbour. Until 1875, this was discussed with the Portuguese who finally got the better end of the stick.

We now jump to the years 1835 – 1837. Then the botanist duo Ecklon & Zeyher (the Dane Christian Friedrich Ecklon and the German Karl Ludwig Philipp Zeyher) published a three-volume book on the vegetable world of southern Africa entitled ‘Enumeratio Plantarum Africae Australis Extratropicae’. In part 3 (1837) we find the following ‘description’:

“KALANCHOE delagoensis. — Exemplum unicum et mutilum Cel. Commodore Owen ad „Delagoabay” legit et nobiscum communicavit. Flor. Jun. — Flores saturate rosei JUN. 1836”.

Mind you, this is the full text. The actual description only consists of the 3 words: Flores saturate rosei. In any case, it can be seen from the text that there was only one mutilated (damaged) specimen and that it ended up at Ecklon &Zeyher via Captain Owen from Delagoabay. I then assume that this happened after Forbes died in August 1823.

For me, the question now is when and where botanist Forbes found the plant. Like all Kalanchoes, K. delagoensis is a short-day plant and it blooms in winter. In the southern hemisphere that’s the case between May and October. Forbes was first in Delagoa from early September to December 5. If the plant had been in bloom at the time, why would botanist Forbes have kept that cutting on board for more than six months? He had a habit of sending all his planting material to England. After the first stay, Forbes was not back in Delagoa until early March 1823. Then the plant is probably not yet in bloom. So how could he have found a flowering plant in Delagoa? Maybe he didn’t find it until July when he was preparing for the expedition upstream along the Zambezi River?

Forbes’ notes may provide more clarification about the find, but they are lodged with the Horticultural Society and are not available on the internet.

In 1862, 25 years after the description of Ecklon & Zeyher, the Irish botanist William Henry Harvey (1811-1866) in the Flora Capensis published the same plant under the name Bryophyllum tubiflorum. Harvey knew the earlier description of Ecklon & Zeyher (he also worked with Ecklon), but according to him this description was invalid and Kalanchoe delagoensis was therefore a so-called nomen nudum, a name without a valid description. Harvey not only chose to place the plant in the genus Bryophyllum because the flowers have only 4 petals, but he also changed the species name delagoensis to tubiflorum. Thinking that the plant should have a different genus name may be understandable, but changing the species name without a proper reason is, in my opinion, very disrespectful to your predecessors. The following is his description:

B. tubiflorum (Harv.) ; leaves unknown; corolla thrice or four times as long as the sharply 4-cleft calyx, its segments broadly oblong, very blunt or truncate ; stamens as long as the tube of the corolla. Kalanchoe Delagoensis, E. $ Z.! 1955.

HAB. Delagoa Bay, Forbes! (Herb. Sond.) Of this very remarkable plant a portion of a denuded branch, and a part of a dense, probably thyrsoid, inflorescence exist in Herb. Sonder. The internodes are scarcely an inch long, and there are 4 cicatrices, indicating whorled leaves, at each node. calyx 3 lines long. corolla uncial, bright red, its lobes almost square, 2½ lines long.

This description shows that Harvey described exactly the same damaged specimen as Ecklon &Zeyher. We are also briefed on the nature of the damage: the material consists only of a defoliated stem (“leaves unknown”) and part of the inflorescence. If Harvey had seen the tubular leaves, he might have called the plant B. tubifolia instead of B. tubiflora. Tubular flowers are not uncommon in kalanchoe-like plants, but tubular leaves may be unique. For the truly curious among the readers: “Herb. Sond”. in the description above refers to the herbarium of the German botanist Otto Wilhelm Sonder, co-author of the Flora Capensis.

More than a century later, in 1985, Toelken argued that the 3 words of Ecklon & Zeyher were enough to distinguish the plant from its closest relatives so that, according to him, because the name K. delagoensis was the first published one, it should be considered the valid one, rendering the name B. tubiflorum of Harvey invalid. It’s called a nomen invalidum.

There is also Kalanchoe verticillata, described by George Francis Scott-Elliot in 1891 (later renamed Bryophyllum verticillatum by Alwin Berger). According to current views, this is synonymous with Kalanchoe delagoensis.

The stems of K. delagoensis become up to 1.2 m tall and the cylindrical leaves are 1.5 to 12 cm long and 2-6 mm in diameter. The number of teeth at the tip of the leaves is 2 to 9. The terminal inflorescence reaches a height of 30 cm. The bell-shaped flowers are brick-red to reddish violet-gray and 2 to 3 cm long.

Kalanchoes are short-day plants, and the flower-stalk begins to develop around mid-November in my greenhouse.

The plant puts all it has into this flowering and deteriorates dramatically during it. From the top of the plant down, the leaves are ‘drained’ and they start drooping more and more. By the time the plant has finished flowering -this can take some five weeks- there is only little left of it. But, in that pathetic little pile there are still many adventitious plantlets which under favorable conditions will quickly develop into new plants.

With this plant, it seems completely unnecessary to discuss its growing conditions. Nevertheless, I would like to point out that you get the most beautifully developed plants by giving it a lot of light (but not sun all day). It is also not wise to let the plant dry out. It will survive, but it’s definitely not going to get any prettier. It seems that the plant can tolerate a bit of frost. I never tried it.

As mentioned above, the Bryophyllums come from Madagascar and in particular the southwest. F. Vandenbroeck describes in Succulenta that the plant grows noticeably more poorly and stockier in Madagascar’s natural biotopes than in our collections. There were hardly any adventitious plantlets to be seen and the plants did not grow rank. Moreover, the flower colour was much brighter than with us.

Thanks to its phenomenal power of reproduction, K delagoensis has spread all over the world. For example, in the Canary Islands, where I have often found the plant escaped from nearby gardens and from the craving of the garden owners to regulate, much like Crassula multicava discussed earlier in this series.

In many countries, the plant is on the list of weeds. The plant became established in the Australian states of New South Wales and Queensland around 1940. As a short-day plant, K. delagoensis also blooms there in winter (from May to October) which is the dry season and therefore also a time of food shortages. As a result, the cattle often feast upon this very plant, which can result in deadly poisoning. (For the specialists: the poison belongs to the bufadienolide cardiac glycosides). The animals die within 1 to 5 days. In New South Wales, for example, 125 animals died after eating this Kalanchoe in 1997. Rapid intervention by a veterinarian can save the cattle, but that is a pricey issue. Medication for 1 cow costs $70 and this does not include the fee for the vet. That is why no mean measures have been taken.

The legal requirement is: “The plant must be fully and continuously suppressed and destroyed and the plant must not be sold, propagated or knowingly distributed”.

Owning or selling the plant is an offense unless you have a permit. The same measures apply to the hybrid K. daigremontiana x delagoensis (Kalanchoe x houghtonii). This hybrid is very similar to the mother plant K. daigremontiana, but the leaves are much narrower, about 1 cm rather than 4 cm. A characteristic of this hybrid is the sharp incision in the middle of the leaf.

Pest control is done with herbicides and also organically with the South African citrusthrips. A weevil, Alcidodes sedi, is also sometimes used for biological control.

For a plant that is spread worldwide, of course, many names are in circulation. In English e.g.: Chandelier plant, mother of thousands, mother of millions, mission bells, Christmas bells, and friendly neighbour. The latter probably will not be endorsed by the cattle farmers in Australia.

Literature:

Boteler, Thomas (1835). Narrative of a voyage of discovery to Africa and Arabia, Richard Bentley, London.

Ecklon & Zeyher (1837). Kalanchoe delagoensis, Enumeratio Plantarum Africae Australis Extratropicae: 305.

Harvey & Sonder (1862) Flora Capensis 2: 380.

Owen, W.F.W. (1833). Narrative of voyages to explore the shores of Africa, Arabia, and Madagascar, Richard Bentley, London.

Vandenbroeck, F. (1984). De bizarre succulentenwereld van Madagascar, Succulenta 63 (9): 201

Originally published in Succulenta Febr. 2012. Translated from the Dutch by F.N.

Fig. 1 The plants produce miniature plants on the edge of the leaves.

Fig. 1 The plants produce miniature plants on the edge of the leaves.

Fig. 5 Anyone who sees K. delagoensis in bloom can hardly imagine that many consider it a troublesome weed.

Fig. 5 Anyone who sees K. delagoensis in bloom can hardly imagine that many consider it a troublesome weed.

Fig. 6,7,8 In habitat near Ambovombe. Photos F.N.

(Other photos by Theo Heijnsdijk)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

picture 4

picture 4